Naomi Hyman was my Abuela. I first met her when I was about three years old. She lived with or near us for 15 years before escaping from her three daughters in New York City and returning to the island that she loved – Jamaica. In all those years, I never understood her – I thought her one of the oddest people I had ever met.

I did have a “Grandma Sice” – who seemed like a real grandma – she hugged me and my brothers a lot; she made us milk and cookies, hot chocolate in the winter; she called us sweet hearts and darlin’s and was always happy when we were around. The thing was, she wasn’t even a family member!

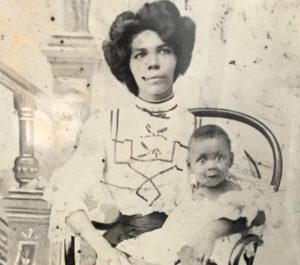

Actually, Naomi was the only one of my natural grandparents who lived to meet her grandchildren. The others had all died in their thirties. So, I was fascinated by this grandmother, Naomi – this strange human being with such odd habits. At about the age of ten, I began to ask my mother questions. Why was she always talking about going back to Jamaica? I thought she came from Cuba. Why did she always wear 3 or 4 blouses, and 3 or 4 skirts – with her head wrapped up in at least 2 kerchiefs. Once in a while, I saw her hair – she had long braids that she could sit on, jet black, wavy, with a few strands of white running through it. Beautiful! Why did she smoke Camel cigarettes so incessantly?

And why did she always seem so distant, so disengaged, so discontent? As her story unfolded, I learned that she was someone who had never accepted the life she lived – she always thought that she was meant for another life – another set of circumstances that were stolen from her. She was a person whose dreams had dried up like Langston Hughes’ “raisin in the sun”. And she refused to accept it.

Naomi’s dream was to be able to read and write and learn a trade that she could use to make her own money without depending on a man, or becoming a servant in other people’s homes.

A modest dream – but one that was not easy to achieve for little girls like Naomi in the late 1800s. Naomi was removed from the home of her grandparents at age ten and sent to serve in the home of a relative instead of attending school, as she had hoped and felt she had been promised. After running away from that situation and immigrating to Cuba, she found that she had little choice but to work as a servant if she wanted to eat. She became pregnant and began having children while still in her teens.

Naomi had four children that belonged to the same father, but refused to marry him – it was not a part of her dream. She worked and lived in other people’s homes until her children were grown.

I often think of my Abuela and wonder what her life, her spirit, would have been like had she been born during my lifetime – a lifetime in which I have seen women – so many of them – able to go to school, earn degrees in all fields at the highest levels. Learning a trade? Today we see ourselves climbing telephone poles, building computers and cars – we are fire persons and police persons. We are soldiers and captains and generals. We are professionals; we run corporations, educational institutions, sports teams, world organizations. We see ourselves in the Vice President of our country! How different a person Naomi might have been if she had just a fraction of these opportunities? In the Caribbean, as well as in the rest of the world, women today are breaking barriers right and left!

When I think of this Abuela now, I think I understand. I last saw her in Tollgate, Jamaica, in the late 1960s, standing in front of a two-room house on the land where she had been born. She was proud to see me and introduce me to all her neighbors, most of them relatives who had lived on that piece of land all their lives. “Dis is my granddaughter from de United States – she’s a Teacher – graduated from University.” She waved her hand expansively to indicate to me that all the land I could see around me had belonged to her grandparents. She gave me a bag of mangoes picked from her own tree. Her eyes twinkled; she seemed content at last.

Create Personal Account

December 22, 2025 - 6:15 pm ·Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks! https://accounts.binance.com/register-person?ref=IHJUI7TF

Enregistrement à Binance

December 25, 2025 - 1:27 am ·Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good. https://accounts.binance.info/sk/register?ref=WKAGBF7Y

create binance account

December 28, 2025 - 5:14 pm ·Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?